Kinship has worked with the Scottish Government on a co-branded Kinship Friendly Employer scheme toolkit to support Scottish employers wanting to create positive change for kinship carer workers.

Read our latest news, stats and reports on kinship care in England and Wales.

Kinship has worked with the Scottish Government on a co-branded Kinship Friendly Employer scheme toolkit to support Scottish employers wanting to create positive change for kinship carer workers.

Kinship has today welcomed that support for kinship carers is included within the scope of the government’s long-awaited parental leave review.

Kinship's Practice Lead, Tim Fisher, reflects on discussions from our Knowledge Exchange event about the kinship care local offer and the value of co-production in local authorities.

Kinship is pleased that the government is today finally revealing more details about the long-awaited £40 million pilot of financial allowances for kinship carers in up to 10 local authority areas in England, following last week’s Spending Review.

A dedicated member of the Kinship staff team has been awarded an MBE in the King’s Birthday Honours for her ‘services to kinship care and for advocating for and supporting families.’

Kinship Cymru was delighted to attend the AFKA Cymru Annual Conference on Wednesday 10 June 2025, connecting with colleagues from across the third sector and local authority organisations in Wales.

In response to the government’s Spending Review announcement, we have released the following statement.

Kinship is celebrating winning the best charity advocacy campaign at the PR Week, Campaign and Third Sector ‘Purpose Awards’ which recognises exceptional and powerful projects that make a profound impact and a real difference.

Kinship's new research 'Making work pay for kinship carers' reveals nearly half of kinship carers (45%) lose jobs and careers when they step up to raise a relative or friend’s child to stop them going into care.

BBC Gladiators winner Joe Fishburn paid tribute to all the ‘unsung heroes’ like the grandmother who raised him when he visited Kinship's Newcastle support group for kinship carers.

The government's Children's Wellbeing and Schools Bill is currently making its way through Parliament. But what does it mean for kinship families?

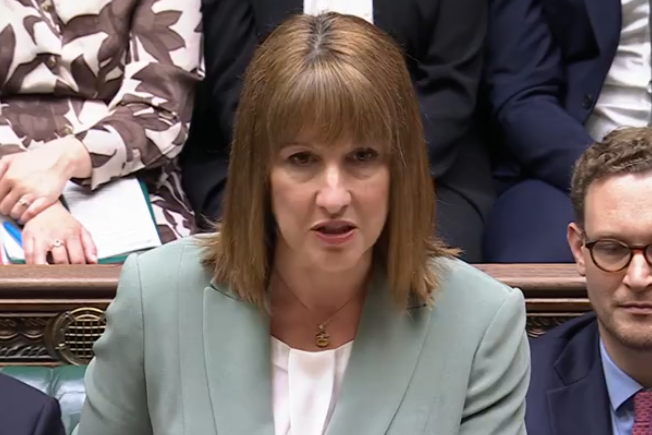

Read our letter, written with sector partners, urging Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson MP to reconsider cuts to the adoption and special guardianship support fund (ASGSF).

On 14 April 2025, the Department for Education (DfE) provided an update on what will happen to the adoption and special guardianship support fund (ASGSF). Read our response.

Our response to the announcement of the renewal of the Adoption and Special Guardianship Support Fund (ASGSF) on 1 April 2025.

New research from Kinship and Oxford University suggests that ethnicity has significantly impacted the experiences of Black and Asian kinship carers when trying to access crucial support.

Kinship have won the 'People's Choice Award' for charities of our size at the 2025 Smiley Charity Film Awards. Find out more and watch our winning film, This is kinship care.

On 18 March 2025, our Young Champions premiered a short film they created about growing up in kinship care. Find out more and watch the film.

On 12 February 2025, over 30 kinship carers marched to the Treasury to demand a financial allowance for all kinship carers. Find out what prompted this action.

New research from Kinship, University of Sheffield and University of Manchester, has calculated the value kinship carers add to the economy at £4.3 billion, despite many still struggling to pay their bills.

The Department for Education (DfE) has introduced paid "kinship care leave", becoming the first government department to achieve the Kinship Friendly Employer Scheme gold standard.

A new poll of our community of kinship carers has revealed that 6 in 10 kinship carers are worried about being able to afford Christmas presents for the children in their care.

Sign up for emails to keep up to date with the information that’s important to you, from support and advice for kinship carers, to our latest news, events and campaigns.